How Do You Really Feel About Money?

Mother was never going to forgive me for this.

I was sixteen years old. She was driving us home from a trip to the shopping mall where she goaded me to try on heels I didn’t want.

In the car, she told me yet again how she looked forward to the day I would grow up to be rich and successful. I hated the pressure.

So I shot back, “No, I don’t want to be rich and miserable. I’d rather be poor and happy.” It was my teenage rebellion against the American Dream.

“You have no idea how much that hurts,” she said.

My mother, an immigrant from South Korea, was recently divorced. She worked non-stop in a nail salon to keep a roof over three daughters. Father was out of the picture. We got by, but money was always tight.

I was hurting too, and I blamed money and my parents’ striving for it for my pain. I didn’t understand adult responsibilities or what my mother endured to make ends meet.

It was easier to play the blame game than to admit how little I understood and how much I yearned for what I could not have.

“Poor and happy” is a lie I bought into and wielded like a weapon because the truth hurt too much.

The truth, of course, is that my mother did her best so that I could do better.

For years after this, I had mixed feelings about money. I had trouble accepting that I deserved happiness and wealth as my mother wished for me (this was before therapy, I might add).

Looking back, it’s no surprise that I bungled my salary negotiation when I was in my twenties and dangerously naïve.

For sure, there were structural inequities and implicit bias to blame. But I also brought to the negotiating table muddled feelings about money and unquestioned assumptions about how to ask for money. It was like I marched right into battle with a gunshot wound in the foot.

Laura Fredricks, fundraising expert and author of The ASK: How to Ask for Support for Your Nonprofit Cause, Creative Project or Business Venture, addresses this headfirst on the very first lines of her book. She says:

“Perhaps the most important part about asking for money is understanding your views on money…

It is essential that we explore our own values of what money means to us, and ask importantly, why we feel we deserve to get what we ask for. This feeds directly into why many people hesitate and fear to make an Ask.”

Recently, I was sharing life goals with a girlfriend over tacos and sangria. She wasn’t sure what she wanted out of life. When I told her that I do want to be rich and successful (because mother was right), she cringed.

She warned me, “More money; more problems. And it brings power, you know, which is bad.”

It made me want to both laugh and cry, because she reminded me of my sixteen-year-old self aspiring for poverty out of spite. I knew no amount of social science research, gender wage gap data, or speechifying would convince her to step up and ask for more.

Not until she gives up the belief that money and power are bad, rather than resources she can use for good.

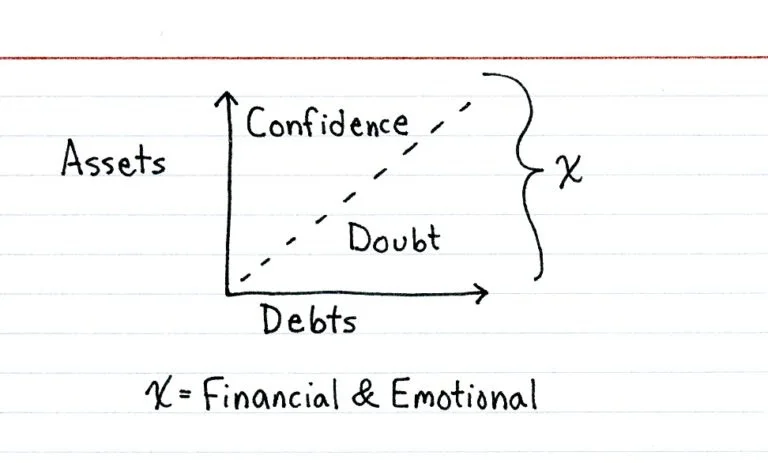

What we believe and feel about money has a huge impact on our negotiations, because it shapes our expectations.

Case in point, a study conducted at Harvard Business School showed that the main determinant of graduates’ salaries and bonuses was their expectations. The more ambiguous their expectations, the bigger the discrepancy between male and female graduates.

So I have to ask: Dear reader, what does money mean to you?

Answering this might be uncomfortable. You, too, may have to revisit some emotionally charged memories. But no bones about it, it’s homework you must do before sitting down at the negotiating table.

You must question assumptions and myths about money that hold you back from abundance. Ask yourself - why not you?

Then go make the ask. Make it rain.

P.S. She forgave me. Whew.